First-Year Graduate Students in Physics and Astronomy: Characteristics and Background

The number of first-year students enrolled in US physics graduate programs has remained relatively stable in recent years and was around 3,200 students in the 2018-19 academic year. There were 241 first-year graduate students enrolled in US graduate astronomy programs in the 2018-19 academic year. Most first-year graduate students held an undergraduate degree in physics or astronomy and felt well or adequately prepared for their graduate studies. The majority of first-year students were funded with teaching assistantships and received full tuition waivers. Their long-term employment goals varied considerably by both a student’s highest anticipated physics degree and citizenship status.

This report examines the demographics, educational background, financial support, teaching assistant experience, and career goals of first-year graduate students enrolled in physics and astronomy departments in the US. For this report, we define first-year graduate students as individuals who have spent fewer than two years within a department and includes students who may have transferred or previously earned a graduate degree at a different institution. This report frequently compares first-year graduate students enrolled in departments that offer a doctorate (referred to as PhD departments) with students enrolled in departments that offer a master’s as their highest graduate-level degree (referred to as master’s degree–only departments).

The data presented in this report are drawn from two sources. Data on the number of physics and astronomy students enrolling in US graduate programs come from the annual American Institute of Physics (AIP) departmental Enrollments and Degrees survey and includes enrollment data through the 2018-19 academic year. Data concerning student background and educational experiences come from AIP surveys of first-year physics and astronomy graduate students. First-year students were surveyed in 2 consecutive academic years, 2014-15 and 2015-16.

Data for physics and astronomy students were collected separately for both data sources. The first portion of this report addresses first-year physics graduate students and the second part discusses first-year astronomy students.

Number of First-Year Graduate Students in Physics

According to the AIP Enrollment and Degrees Survey, the number of first-year students enrolled in physics graduate programs has remained relatively stable in recent years (see Figure 1). In the 2018-19 academic year, there were about 3,200 first-year physics graduate students enrolled in one of the 258 graduate physics programs in the US. Ninety percent of the students were in enroll at one of the 201 PhD departments and the remaining students were enrolled in one of the 57 master’s degree-only departments.

Figure 1

Since the early 2000s, the overall percentage of non-US citizens enrolling in US physics programs has remained relatively stable at over 40%. Figure 2 shows the trend in the representation of non-US citizens by the highest graduate degree offered by departments. Non-US citizens have consistently represented a larger percentage of the first-year students enrolled in PhD departments then at master’s degree–only departments.

Figure 2

In the academic years of 2014-15 and 2015-16, 44% of first-year physics graduate students were non-US citizens. Over 70% of international students came to the US from countries in Asia, particularly China and India (see Table 1).

Table 1

Women comprised more than a fifth of the first-year physics graduate students in the 2018-19 academic year. The percentage of women among first-year physics graduate students at both PhD departments and master’s degree–only departments has increased slightly since 1995 (see Figure 3). In the 2018-19 academic year, 22% of first-year physics graduate students in PhD departments were women, and 19% of students in master’s degree–only departments were women.

Figure 3

Characteristics of First-Year Physics Graduate Students

First-year graduate students enrolled in master’s degree–only departments tended to be older than students in PhD departments (see Table 2). A large percentage of students enrolled in both types of departments planned to receive a doctorate degree, indicating that many students enrolled at master’s degree–only departments intend to later enroll at a different institution that offers a physics PhD. Over 90% of students were enrolled full time in both PhD and master’s degree–only physics departments. Most students had selected their research subfield by the second half of their first year of graduate study. Eleven percent of students at a master’s degree–only department indicated that selecting a specific subfield was not required for their degree.

Table 2

Educational Background of First-Year Physics Graduate Students

Most first-year physics graduate students had earned a bachelor’s degree in physics or astronomy prior to enrolling in a US graduate physics program (see Table 3). Most students who earned bachelor’s degrees in other subjects majored in engineering and mathematics. About one-fifth of the US citizens among first-year physics graduate students reported starting their undergraduate education at a two-year or community college.

About a quarter of US citizens and half of non-US citizens had previous physics or astronomy graduate-level training at a different institution. A large proportion (30%) of non-US citizens received a physics master’s or equivalent degree from a foreign institution prior to enrolling in their US graduate physics program. There were no gender differences in the educational backgrounds of first-year students.

Table 3

To determine if there was a delay before starting their graduate physics education in the US, we asked first-year graduate students if there was a gap of more than 5 months between receiving their bacheor’s degree and enrolling in a US graduate physics program for the first time. Overall, 42% of first-year physics graduate students reported a delay of more than 5 months. A greater percentage of students enrolled at master’s degree–only departments and non-US citizens had a delay (see Table 4). For the non-US citizens who had delayed their US graduate program enrollment, 46% indicated the delay was a result of having been previously enrolled in a graduate physics program at a non-US institution.

Students were asked to report the length of their enrollment delay. Students at master’s degree–only departments had a half-year longer delay than those at PhD departments, and non-US citizens had a 1.5 years longer delay than US citizens. There were no gender differences in a graduate education delay.

Students who delayed their enrollment were asked to provide open-ended descriptions of what they did between receiving their undergraduate degree and enrolling in a US physics graduate program. Many international respondents reported that they were enrolled in a master’s program outside of the US. Of those who were employed during the delay, most respondents worked in teaching positions. Some international respondents worked as faculty members or lecturers in departments overseas. Both US and non-US citizens worked as high school teachers, teaching assistants, or tutors. Some respondents worked in research positions at their undergraduate institutions or at national laboratories, while still others used their science skills in industry positions. Not all respondents held a position relevant to their degree and were employed in retail or in other jobs outside of science.

Table 4

Respondents participated in many other activities during their delay. Some focused on the graduate school application process and prepared for required entrance exams such as the GRE, while still others relaxed, spent time with family, traveled, or cared for their children.

The first-year physics graduate students were asked to rate how well they felt their undergraduate education prepared them for their graduate studies (see Figure 4). Overall, 89% felt adequately or well prepared. First-year students who had received a bachelor’s degree in a field other than physics or astronomy, who were women, or who had a delay (of more than 5 months) between receiving their bachelor’s degree and starting their US graduate education reported feeling less prepared. There were no differences in preparedness between US and non-US citizens.

Figure 4

Financial Support of First-Year Physics Graduate Students

First-year physics graduate students received financial support from a variety of sources. Overall, 64% had a teaching assistantship as their primary type of financial support, 18% had a fellowship, and 9% had a research assistantship.

There were some differences between first-year graduate students attending PhD-granting departments and master’s degree–only departments in the types of financial support they received (see Table 5). A greater percentage of students at PhD departments received fellowships, while a greater percentage of students at master’s degree–only departments relied on financial support from family members, personal savings, or loans. In addition, a smaller percentage of students with assistantships or fellowships at master’s degree–only departments received full tuition waivers.

Table 5

When comparing men and women, a greater percentage of women (22%) received fellowships as their primary type of financial support than did the men (16%). There were no other differences by gender or citizenship in the types of financial support, tuition waiver status, or stipend amount.

The median stipends or salaries for first-year physics graduate students enrolled at PhD departments were considerably higher than those at master’s degree–only departments (see Figure 5). Students at PhD departments whose primary source of support was a teaching assistantship or research assistantship had a median stipend of $20,000 a year. PhD students with fellowships were generally better financially supported with a median stipend of $26,000. At master’s degree–only departments, the median teaching assistantship and research assistantship stipend was around $10,600 and $14,500, respectively. The survey did not capture the number of service hours students were required to work for these assistantships. It is possible some of the differences in stipend levels are a result of differences in required work load.

Figure 5

Teaching Assistantship Experiences of First-year Physics Graduate Students

Graduate students who worked as teaching assistants (TAs) were asked if they received any formal instruction in teaching or were formally supervised and evaluated. Almost three-quarters of the TAs had received formal teaching instruction (see Table 6). The most common type of evaluation TAs received was from their students, with 79% receiving such evaluations. About half of the TAs received formal supervision or evaluations from a faculty member, and 38% received formal supervision or evaluations from an experienced teaching assistant.

Teaching assistants were also asked what tasks they performed during their work. Almost all TAs were required to grade class materials. Supervising or running lab sections, as well as holding office hours, were other more common tasks that were performed.

Table 6

Future Career Plans of First-year Physics Graduate Students

First-year physics graduate students were asked where they would like to be employed 10 years after receiving their highest anticipated physics degree. There were differences in career aspirations by the students’ highest anticipated physics degree and citizenship (see Table 7). A greater percentage of students who intended to end their physics graduate training with a master’s degree aspired to work in the private sector or medical field, while students intending to receive a PhD were much more likely to aspire to work at a university. US citizens were more likely to indicate a desire to work in the private sector, government, or the medical field than non-US citizens. The majority of non-US citizens aspired to work at a university. A greater percentage of US citizens than non-US students, and a greater percentage of students intending to receive a PhD versus those intending to receive a master’s degree were unsure about their future employment goals.

First-Year Astronomy Graduate Students

AIP’s Enrollment and Degrees Survey found that there were 241 first-year graduate students enrolled in US graduate astronomy programs in the 2018-19 academic year (see Figure 6). Compared to first-year physics student enrollments, there was a greater percentage of women and US citizens among first-year astronomy graduate students. In the 2018-19 academic year, 40% of first-year astronomy students were women (see Figure 7), and 21% were non-US citizens (see Figure 8). This compares to 22% women and 42% non-US citizens among first-year graduate physics students. In the 2018-19 academic year, only three astronomy departments offered a master’s as their highest degree; as a result, we are not reporting any analyses comparing master’s degree–only and PhD departments.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

All first-year astronomy graduate students were enrolled full time., virtually all planned to receive a doctorate degree, and most had selected their research subfield or specialty (see Table 8). The median age of first-year astronomy graduate students was around 23.

Table 8

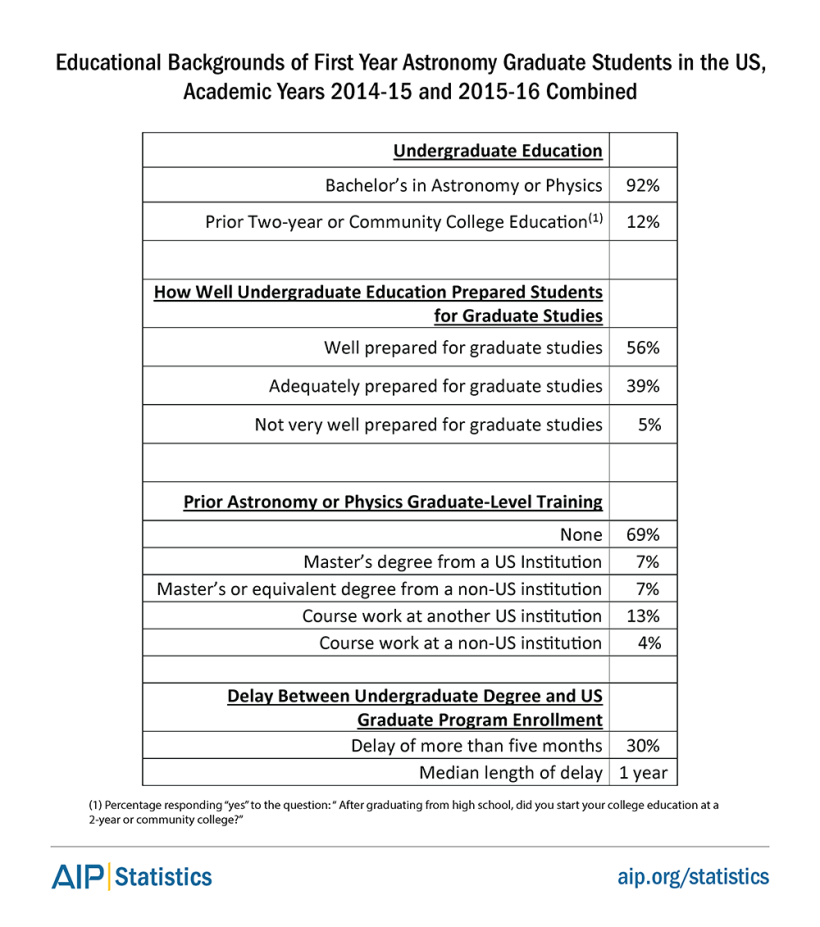

The majority (92%) of first-year astronomy graduate students held a bachelor’s degree in physics or astronomy, and 12% indicated they started their undergraduate education at a two-year or community college (see Table 9). Almost all (95%) of first-year astronomy graduate students felt well or adequately prepared for their graduate studies.

About one-third of the first-year astronomy graduate students had previous graduate-level training in physics or astronomy prior to enrolling in their current department. Most students with previous training had taken graduate-level coursework at another institution.

Thirty percent of first-year astronomy students had a delay of more than 5 months between receiving their undergraduate degree and enrolling in a graduate program in the US, with a median delay length of 1-year.

Table 9

About half of first-year astronomy students held teaching assistantships as their primary type of financial support (see Table 10), which is a smaller percentage than first-year physics students (65%). However, a greater proportion of first-year astronomy students had a research assistantship or fellowship then their physics counterparts. The vast majority of first-year astronomy students received a full tuition waiver.

Table 10

First-year astronomy students with fellowships reported the highest stipend amounts (see Table 11). Because we do not know the number of hours students are required to work in their assistantships, the median stipend amounts of first-year astronomy students are not directly comparable to those received by the first-year physics students.

Table 11

First-year astronomy students who worked as TAs were asked if they received any formal instruction in teaching or were formally supervised and evaluated. About half (54%) indicated they had received formal teaching instruction (see Table 12). Like physics TAs, the most common source of evaluations came from their students (73%). About a third of the TAs received formal supervision or evaluations from a faculty member, and a quarter received formal supervision or evaluations from an experienced TA. Also similar to physics TAs, the most common responsibilities of astronomy TAs centered around grading class materials, holding office hours, and supervising lab sections.

Table 12

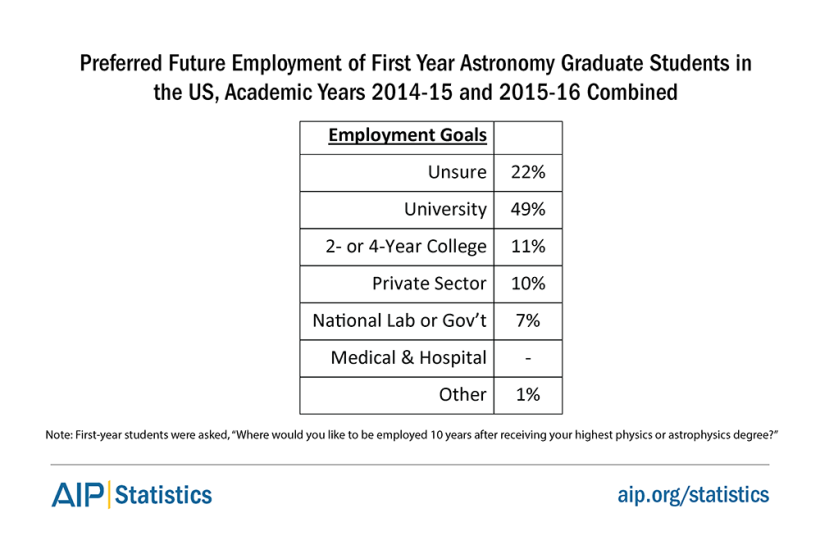

When first-year astronomy students were asked about their career aspirations 10 years in the future, about half of students wanted to work at a university with graduate-level programs (see Table 13).

Table 13

Survey Methodology

Each fall the Statistical Research Center conducts its Survey of Enrollments and Degrees, which asks all degree-granting physics and astronomy departments in the US to provide information concerning the numbers of students they have enrolled and counts of recent degree recipients. At the same time, we ask for the names and contact information for students currently enrolled in their graduate programs.

Much of the data in this report comes from physics and astronomy graduate students who were identified as being new to a department in the academic years 2014–15 and 2015–16. An initial invitation to participate in the survey was sent to graduate students in April of their first year at the department. Non-responding students were contacted with up to three additional invitations. Respondents were considered first-year graduate students if they had completed fewer than two years of graduate study at the department they were currently attending, regardless of whether they had been previously enrolled at a different graduate-level program either within or outside the US.

According to the findings from the Survey of Enrollments and Degrees, there were 3,232 first-year physics graduate students enrolled in the 2014-15 academic year and 3,210 in the 2015-16 academic year. We did not receive contact information for all known first-year physics students in the two student cohorts. We received responses from approximately 30% of the students for whom we believe we had valid contact information. As a result, we received usable survey responses from 20% of the total number of known first-year physics students in the two academic years that were the focus of this study.

According to the findings from the Survey of Enrollments and Degrees, there were 187 first-year astronomy graduate students enrolled in the 2014-15 academic year and 198 in the 2015-16 academic year. We did not receive contact information for all known first-year astronomy students in the two student cohorts. We received responses from approximately 46% of the students for whom we believe we had valid contact information. As a result, we received usable survey responses from 32% of the total number of known first-year astronomy students in the two academic years that were the focus of this study.

We thank the many physics and astronomy departments and graduate students who made this publication possible.

The tables and figures in this report are available for download from www.aip.org/statistics

e-Updates

You can sign up to receive email alerts that notify you when we post a new report. Visit http://www.aip.org/statistics/e_updates to sign up.

Follow us on Twitter

The Statistical Research Center is your source for data on education, careers, and diversity in physics, astronomy, and other physical sciences. Follow us at @AIPStatistics.

First-Year Graduate Students in Physics and Astronomy: Characteristics and Background

By Patrick Mulvey, Anne Marie Porter, and Starr Nicholson

Published: November 2019

A product of the Statistical Research Center of the American Institute of Physics

1 Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740

stats [at] aip.org